Born in Foreign Parts - Lewis Donegani of Dublin and Livorno

Published by K L Donegani in Early Doneganis UK & Eire · 27 October 2020

Tags: Marble, Livorno, Leghorn, Dublin, Montecatini, Guido, Donegani

Tags: Marble, Livorno, Leghorn, Dublin, Montecatini, Guido, Donegani

Photo: Custom House, Dublin. Courtsey of the National Library of Ireland.

It is no surprise that the Irish genealogical sources for the early ninteenth century contain many Donegan, Donagon and Doneghan (etc) families, as this is not an unusual family name in Ireland. However, one Donegani does appear regularly in the Dublin trade directories from the 1830s to the late 1870s - the business of Lewis Donegani, later Donegani and Hickey. In the earlier years this company was a wholesaler of imported Italian marble with offices in Lower Fleet Street but in the 1840s, the firm moved to 200 Great Brunswick Street (now Pearse Street) and expanded its business activities to include the sale of marble statuary and plaster mouldings as well as a wide range of imported Italian goods.

Surprisingly, despite this enduring presence in the city, there appears to be only one reference to Lewis Donegani in Irish genealogical sources – that of his marriage to Marcella Reilly (or O’Reilly) in Dublin in 1843.[1] Luckily it did not take long to spot a clue to the reason for this dearth of local records - the description of Lewis Donegani in Thom’s Irish Almanac [2] as ‘a merchant of Dublin and Leghorn’, Leghorn being the name then used by the British for the port and city of Livorno in Tuscany. In this blog we’ll take a brief look at the business and family life of the only early, foreign born Donegani we have found in Ireland. To avoid confusion, we will refer to him by his birth name, Luigi.

Luigi Donegani was born in Moltrasio in Lombardy around 1800 but, like many other young comaschi [3], he left home as a young man to travel around Europe working as a hawker. We do not know what he sold but as he reportedly made regular trips home, it is possible that he stocked up with the traditional craft products of the Como region, such as barometers, thermometers, looking-glass and picture frames and jewellery to sell abroad.

We also know that Luigi visited members of his family who were living in Livorno, at that time a flourishing free-port in Tuscany and, after the death of his cousin Giuseppe Donegani in March 1842, he moved to Livorno to take over the family’s trinkets and costume jewellery shop.[4] Luigi appears to have been an energetic and ambitious business man. He turned the trinket shop into an office for his expanding business activities which included shipping, the dismantling of ships and exporting a range of Italian products, including those sent to Dublin.

Before we take a closer look at Luigi’s business interests and explore his family connections, let us enjoy a rare treat for a family historian – a contemporary description of our subject:

'Of mediocre stature, rather fat, Donegani walked upright, with a steady step, although not fast due to his body weight. He had the habit of keeping his head tilted, while his changing gaze wandered, acutely uneasy. In his work he was tenacious, to the point of showing impatience in the face of doubtful lingering. He took care of his own affairs directly and only those who had his trust allowed to intervene. The man's character was sober, reserved, modest; he did not like licentious ways nevertheless he blamed them with indulgent good-naturedness.' [5]

Luigi appears in the records of arrivals at the ports of Dover and London showing that he made regular visits from Livorno during the period 1835-1852.[6] As we have no record of him having any business activities in England, we presume he was en route to Dublin. Although passport details were not recorded for every landing, we can see that in December 1835 he travelled on a Tuscan passport whilst in August 1852 he is described as a native of Italy travelling with an Austrian passport (the Italian states, including Tuscany, were under the control of the Austrian Empire at this time). We do not know how long he stayed in Dublin but as his family and the centre of his business was in Livorno, we assume these were relatively short visits.

in order to run a successful business in Ireland, he must have had ‘those who had his trust’ to help him manage his affairs in Dublin. Our findings suggest that he had the support of a small but close-knit group of Irish-Italian families which made it possible to run a successful business without being resident in the country. It has been suggested that Luigi had a sister who married an Irishman and lived in Dublin [7] though we have not yet been able to identify her, she may have provided Luigi with a family and social network. However, the records do suggest that Luigi had a small but essential network of immigrant families from Lombardy helping him to establish and run his business in Dublin.

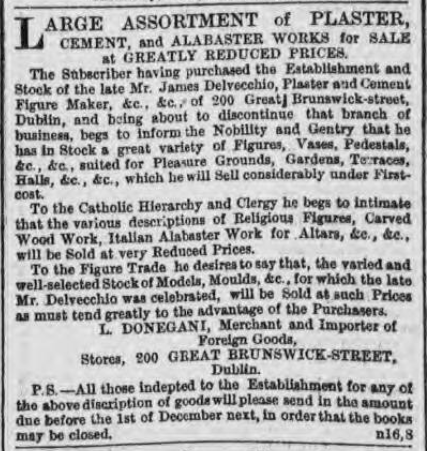

Luigi first appears, as 'Lewis Donegani, Merchant', in the Dublin Post Office Directory of 1838, located at 58 Lower Fleet Street, but later moving to 200 Great Brunswick Street. A closer look at the records for these premises shows links between the Del Vecchio and Donegani families of Como, just as they were in England, Canada and the USA (see Born in Foreign Parts). The Del Vecchio family from Como were in business in Dublin before 1802, with James Del Vecchio selling prints in South Great George Street before moving to Westmorland Street in 1805, where he established a very successful art gallery and auction house. The Del Vecchio family also ran a grocery store at 58 Lower Fleet Street, the address of Luigi’s first office, and manufacturing looking glasses and plaster of Paris. The company expanded in to the manufacture of statues and plaster mouldings at 200 Brunswick Street, where Luigi sold imported marble from around 1847. Luigi also bought-up the remaining stock of the Del Vecchio's plaster and statuary business when James Del Vecchio died and employed James's son Francis and his long-serving Italian warehouseman to run the business in his absence. [8]

Freeman’s Journal, Wed 22 Nov 1865, p.2. Copyright: The British Library Board, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk.

During the 1860s, Luigi expanded the range of his imports, which were usually listed in the Shipping Intelligence reports in the local press, showing how much duty he had to pay on the goods. The Dublin Daily Express listed his imports that had arrived from Leghorn on Saturday 7th February 1863, showing he amount of duty he had to pay:

IMPORTS, - Leghorn – 3 cases, 18 boxes macaroni, L. Donegani 6s.5d; 19 blocks, 259 slabs marble, 25 bales rags, 3 bales hemp, 188 half chests, 59 boxes olive oil, 1 case furniture and 33 tons linseed oilcake. L. Donegani, free.Dublin Daily Express, Mon 9 Feb 1863, p.4,

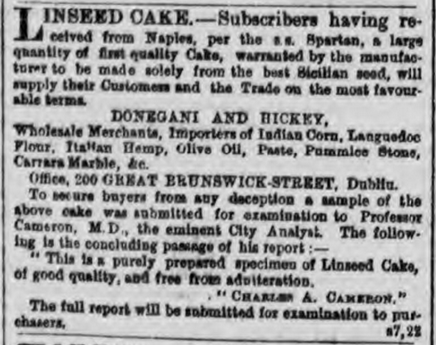

From the mid-1860s, the new business partnership of Donegani and Hickey marketed the ‘scientifically-tested’ Italian Linseed Cake to Irish farmers, but as their advert in the Freeman’s Journal shows, they were now selling a range of Italian goods - Indian Corn, Languedoc Flour, Italian Hemp, Olive Oil, Paste, Pumice Stone and Carrara Marble - from their office at 200 Great Brunswick Street.

Freeman’s Journal, Wed 9 September 1868, p.1. The British Library Board, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk.

We have not yet been able to establish how Luigi came to set up the partnership with Mr Hickey but we do know that a Maria Hickey was a witness to Luigi and Marcella’s marriage in 1843, suggesting a potential social or family connection. Court records and press reports also tell us that Mr John Hickey was connected to the Del Vecchio family, as he was the plaintiff in a series of court hearings relating to “leases for life” held by members of the Del Vecchio family for property in Dublin, including 26 Westmorland Street, [9]

At the meeting of the Loyal National Repeal Association in Dublin in August 1843, two members of the audience, Peter Mackey and Lewis Donegani, declared themselves to be looking-glass manufacturers and natives of Italy who had paid their £1 subscriptions and wished to be members of the Association.[10] We do not know if Luigi ever worked in the looking-glass trade, though it would not be surprising to learn that it was his original trade or that he hawked looking-glasses around Europe as a young man. Peter Mackey was a well-established looking-glass maker in Dublin, appearing in directories as early as 1814.[11] In October 1843, Johanne Mackey was the second witness to Luigi and Marcella’s wedding which suggests Luigi had more than a political or business relationship with the Mackey family. There are examples elsewhere which suggest that Mackey was adopted as an Anglicised version of the Italian (and possibly French) family name Mache [12] and that at least one Mache family originated from Como, so it may be that the Mackey family were also part of a Lombardian community in Dublin.

These few examples from the available historical records suggest that Luigi had a close-knit Irish-Italian network in Dublin - trusted individuals who worked to run his business affairs.

To find out about his family life and the fate of his business empire, we have to look to Livorno.

Luigi and Marcella had four sons and reportedly, two daughters who died young. Two of their sons, Giovan Battista Donegani and Guilio Donegani took on the business of Luigi Donegani Co. after Luigi’s death in 1877. By the late 1890s, they had turned it into a substantial commercial and financial enterprise which included a small copper mine run by the Montecatini Mining Company. After Giovan Battista’s death in 1910, his son Guido Donegani (1877-1947) took control of Montecatini, relocated its headquarters to Milan and led the expansion and diversification of the company, which became the largest producer of agro-chemicals in Italy as well as operating power stations and manufacturing explosives and munitions. Guido Donegani was a member of Parliament, later a Senator, a supporter of the Italian National Fascist Party and an emissary of Mussolini.

[1] Ancestry. Ireland Catholic Parish Registers. St Nicholas’ (Without) Dublin City, Parish Registers 1822-1863, p.81v.,1843, October 9, Loudovicus Donnegani et Marcella Reilly.

Also see: Weekly Freeman’s Journal, Saturday 14th October 1843, p.8, ‘On the 9th instant, by the Very Rev. Gerald Doyle, Catholic Rector of Naas, Signore Suigi (sic) Donegani, of Leghorn, to Marcella, youngest daughter of the late Michael O’Reilly, Esq., of this city.’

[2] Thom’s Irish Almanac and Official Directory, 1864, p.1313 “Donegani, Lewis, merchant, figure, vase and ornament manufacturer, and Leghorn”.

[3] Young men of Como

[4] F. Crimeni, ‘I Donegani. Una famiglia del primo capitalism italiano’, Studi Storici, vol. 38, no. 2 (1997), p.390.

[5] F. Crimeni, ‘I Donegani’, (1997), p.392. Crimeni cites the 1877 publication of Targioni Tozzetti, who gave the eulogy at Luigi’s funeral. He also reports that Luigi’s gravestone bears the memorial ‘Blessed is the rich man who is found without fault: he could do harm and did not’. Translated from Italian using Google Translator.

[6] The National Archives, HO 3: Home Office: Aliens Act 1836: Returns and papers. July 1836-December 1869.

[7] F. Crimeni, ‘I Donegani’, (1997), p.390.

[8] Further information on the marble works is to be found in the University of Glasgow project site, Mapping the practice and profession of sculpture in Britain and Ireland, 1851-1951 <https://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/organization.php?id=msib3_1207735050>

[9] Warder and Dublin Weekly Mail, 24 March 1849, p.1

[10] Freeman’s Journal, 8 August 1843, p. 3. John Hickey was also listed as a subscriber to the Association. The Association sought legislative independence for Ireland under the British Crown

[11] John Watson Stewart, The Gentleman’s and Citizen’s Almanack for the Year 1814, p.72. Entry reads: Mackey (P. and G.) Carvers and Gilders, 34 Skinner-row. Later directories described the company as looking glass manufacturers of 35 Pill Lane.

[12] As an example: John Mackey, who was born in Como, Lombardy around 1816, appears in successive English census returns (in London and Liverpool) from 1861 and 1871 as John Mackey but on his 1845 marriage certificate and in the 1841, 1851, and 1881 censuses he appears as John Mache, even though his sons are shown as Mackey. His early occupation was a looking-glass journeyman. He is described as a wire worker in later census returns.